Class notes: from 16/01/26:

Video: https://youtu.be/SwZ7cDF0hd0?si=LGYp0Tmrrz5haegx

Homework:

Notes regarding the video from Grok:

Overview of Nose Anatomy

The nose is a complex structure comprising the external nose and the internal nasal cavity, which is the superior-most part of the respiratory tract. Beyond its primary role in olfaction (sense of smell), the nose performs critical functions in respiration and protection: it traps and removes pathogens and particulate matter from inspired air, warms and humidifies this air to prevent damage to lower respiratory tissues, and serves as a drainage pathway for the paranasal sinuses and nasolacrimal (tear) ducts. These functions highlight the nose’s integration with multiple systems—respiratory, immune, and even ocular—emphasizing its role in overall homeostasis. Dysfunction, such as blockages or infections, can lead to issues like sinusitis, impaired breathing, or even secondary complications in ear pressure equalization. The anatomy can be divided into external and internal components, with overlapping skeletal, muscular, vascular, and neural elements.

External Nose Anatomy

The external nose is the visible, protruding part that varies in shape among individuals, influencing facial aesthetics and airflow dynamics.

• Key Landmarks:

• Nasal root: The superior end, continuous with the forehead, providing structural continuity.

• Bridge (dorsum nasi): The bony ridge along the midline.

• Apex: The tip of the nose, which is more cartilaginous and flexible.

• Nares (nostrils): Pear-shaped openings leading to the nasal vestibule; they allow air entry and can flare for increased intake during exertion.

• Nasal columella: The tissue separating the nares, connecting the nasal tip to the base.

• Ala nasi: Cartilaginous “wings” bounding the nares laterally, contributing to nostril shape and mobility. These features not only facilitate breathing but also play roles in cultural and evolutionary contexts, such as adaptations for different climates (e.g., narrower nares in colder environments to warm air more efficiently). Variations can lead to cosmetic concerns or functional issues like nasal obstruction.

Skeletal Structure

The nasal skeleton provides support and shape, blending rigid bone for protection with flexible cartilage for adaptability.

• Bony Components: Include the nasal bones (forming the bridge), parts of the frontal bone (at the root), and maxilla (lateral support). These bones protect underlying structures and anchor facial muscles.

• Cartilaginous Components: Comprise two lateral cartilages (supporting the sides), two alar cartilages (forming the ala nasi), smaller alar cartilages, and the septal cartilage (midline divider). This cartilage allows for flexibility during facial expressions or impacts, reducing fracture risk compared to bone. The hybrid structure ensures durability while permitting movement, but it’s vulnerable to trauma (e.g., nasal fractures common in sports), which can disrupt airflow or cause epistaxis (nosebleeds). Developmentally, these elements arise from neural crest cells, linking nasal anatomy to broader craniofacial embryology.

Muscles of the Nose

Small muscles associated with the external nose enable subtle movements, primarily for facial expression and nostril control, all innervated by branches of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII).

• Procerus: Depresses the medial eyebrows and wrinkles the skin over the superior dorsum, contributing to expressions like frowning or concentration.

• Nasalis: A sphincter-like muscle with two parts:

• Transverse part: Assists procerus in compressing the nasal bridge.

• Alar part: Flares the nares, increasing airflow during heavy breathing (e.g., exercise or emotional states).

• Depressor septi nasi: Aids the alar nasalis in flaring the nares and depressing the septum. These muscles are integral to non-verbal communication and respiratory adaptation. Weakness, as in facial nerve palsies (e.g., Bell’s palsy), can impair nostril flaring, leading to breathing difficulties. From a comparative anatomy perspective, similar muscles in animals enhance scent detection, underscoring evolutionary ties to olfaction.

Innervation of the External Nose

Innervation is divided into sensory (for touch and pain) and motor (for muscle control), reflecting the nose’s dual sensory and expressive roles.

• Sensory Innervation: Provided by the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V):

• External nasal nerve (branch of ophthalmic nerve, V1): Supplies the skin of the dorsum, nasal ala, and vestibule.

• Infraorbital nerve (branch of maxillary nerve, V2): Innervates the lateral aspects. This setup ensures protective reflexes, like sneezing in response to irritants. Implications include trigeminal neuralgia, where nerve irritation causes severe facial pain.

• Motor Innervation: Via the facial nerve, as noted for muscles. Damage here affects expressions, with broader implications for social interactions.

Vascular Supply of the External Nose

The nose has a rich blood supply to support its warming and humidifying functions, but this also makes it prone to bleeding.

• Arterial Supply:

• From maxillary and ophthalmic arteries (internal carotid branches) for skin.

• Septum and alar cartilages from angular and lateral nasal arteries (branches of facial artery, from external carotid).

• Venous Drainage: Primarily via the facial vein into the internal jugular vein. The abundance of vessels aids in rapid tissue repair but increases epistaxis risk, especially in dry environments or with hypertension. Anastomoses (connections) between arteries heighten this vulnerability.

Paranasal Sinuses

These air-filled extensions from the nasal cavity are embedded in surrounding bones, named accordingly: frontal (in frontal bone), maxillary (in maxilla), sphenoid (in sphenoid), and ethmoid (in ethmoid).

• Functions: Humidify inspired air, lighten the skull (reducing head weight for upright posture), support immune defenses (via mucus-trapping), and add vocal resonance (affecting speech timbre). These roles integrate with respiratory and phonological systems; for instance, sinus congestion alters voice quality.

• Drainage:

• Frontal, maxillary, and anterior ethmoidal: Into the middle meatus via the semilunar hiatus (a crescent-shaped groove).

• Middle ethmoidal: Onto the ethmoidal bulla.

• Posterior ethmoidal: At the superior meatus.

• Sphenoid: Through the posterior roof, uniquely not via lateral walls. Blockages can cause sinusitis, with pain radiating to teeth (maxillary) or eyes (ethmoidal). Variations in sinus size influence susceptibility; larger sinuses may drain better but are more prone to infection spread.

Nasal Cavity Structure and Regions

The nasal cavity extends from the nares to the nasopharynx, divided into three functional regions.

• Vestibule: Area within the nares, lined with skin and hairs for initial filtration.

• Respiratory Region: Lined with respiratory epithelium (ciliated cells for mucus movement), containing conchae and meatuses for air conditioning.

• Olfactory Region: At the apex, lined with olfactory cells and receptors for smell detection. This zoning optimizes efficiency: filtration first, then conditioning, finally sensing. Implications include allergies disrupting the respiratory region or anosmia (loss of smell) from olfactory damage (e.g., post-viral).

Lateral Walls and Conchae

The lateral walls feature three conchae (turbinates)—superior, middle, and inferior—curved bony shelves increasing surface area.

• Functions: Enhance contact between air and mucosa for humidification; disrupt laminar airflow into turbulent patterns, prolonging exposure for better warming (up to 37°C) and moisture addition (near 100% humidity).

• Meatuses: Spaces beneath conchae where sinuses drain. This design is energy-efficient for respiration but can hypertrophy in chronic rhinitis, causing obstruction. Edge cases include concha bullosa (air-filled concha), a variant that may require surgical correction.

Additional Openings and Foramina

• Nasolacrimal Duct: Drains tears into the inferior meatus, preventing overflow (e.g., during crying); blockages cause epiphora (excess tearing).

• Eustachian Tube: Opens into the nasopharynx at inferior meatus level, equalizing middle ear pressure; dysfunction leads to ear infections or barotrauma (e.g., during flights).

• Cribriform Plate (Ethmoid Bone): Perforated roof allowing olfactory nerve fibers; fractures risk CSF leaks.

• Sphenopalatine Foramen: At superior meatus, transmits sphenopalatine artery, nasopalatine, and superior nasal nerves.

• Incisive Canal: Connects to oral cavity, passing nasopalatine nerve and greater palatine artery. These connections underscore the nose’s role in craniofacial integration, with implications for procedures like endoscopy.

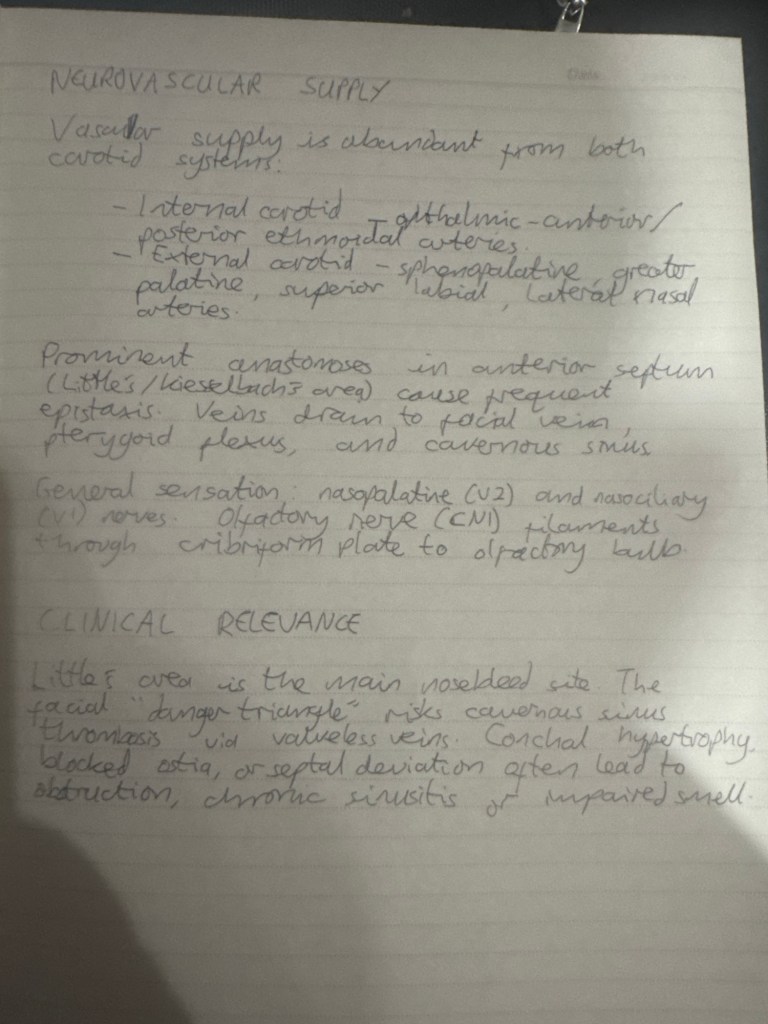

Detailed Vascular Supply of the Nasal Cavity

To humidify and warm air, the cavity receives blood from both internal and external carotid arteries.

• Internal Carotid: Ophthalmic artery branches into anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries, entering via cribriform plate.

• External Carotid: Branches include sphenopalatine, greater palatine, superior labial, and lateral nasal arteries.

• Anastomoses: Prominent in anterior nose (Little’s or Kiesselbach’s area), a common epistaxis site.

• Venous Drainage: To pterygoid plexus, facial vein, and cavernous sinus; this pathway risks infection spread to the brain (e.g., cavernous sinus thrombosis).

Detailed Innervation of the Nasal Cavity

• Special Sensory (Olfaction): Olfactory nerves (cranial nerve I) carry smell to the olfactory bulb atop the cribriform plate; damage causes anosmia, impacting taste and safety (e.g., detecting smoke).

• General Sensory: Nasopalatine nerve (from maxillary, V2) to septum/lateral walls; nasociliary nerve (from ophthalmic, V1).

• External Skin: Trigeminal nerve. This functional division allows precise sensation; nuances include referred pain (e.g., sinus issues mimicking migraines).

Fun Fact and Additional Notes

• Epistaxis is the medical term for nosebleed, often from Little’s area due to its vascularity. The video emphasizes educational resources like Kenhub’s Atlas for deeper study, highlighting inclusive illustrations. Comments from viewers note the content’s clarity for learning, though some suggest slower narration for better comprehension. Overall, this anatomy underscores the nose’s multifaceted role, with clinical relevance in ENT medicine, allergies, and even forensics (nasal morphology in identification).